As we noted in our last book list (a selection of titles chosen by renowned publishers, editors, and photographers), we are drawn to work that inspires the artists who inspire us. Perhaps we feel that by studying the art that sparks their creativity and their vision, we will feel some of the same inspiration—or maybe these new discoveries offer novel insights on the images that captivate us. Either way, we are always asking photography experts to tell us about the work that they find moving and exciting. So, we reached out to our favorite curators and gallerists and asked them to tell us about the books that inspired them this year. After all, these are the people who help decide what work we should be looking at and how that work is presented.

Below you’ll find a journey across India (and through the pages of the country’s national epic); a brilliant catalogue that accompanied one of the “most complex (and genius)” exhibitions of 2017; important and overlooked stories from across Europe, the Middle East, South America; and much more. We hope you enjoy this diverse and wide-ranging selection and find some inspiring (and unfamiliar) books and publishers for further readings in the new year.

You can discover the Top 11 “critically acclaimed” books from 2017 as well as the favorites from photographers, publishers, and editors in our previous coverage of the best books from 2017. Enjoy!

—Alexander Strecker, Managing Editor

Please note that you can scroll to the bottom of this article to see 72 photographs carefully chosen from the 23 selected books.

Yogananthan has promised seven books in this series inspired by the ancient Sanskrit text, the Ramayana. Echoing the text, the artist travels from north to south India photographing revealing moments from daily life, moving fluidly between landscape, observed vignettes, and portraiture. The third volume in the series, titled Exile, tells the story of how the protagonist, Rama, spends 14 years in the woods while banished from his kingdom. The wonderfully subtle photography, design, and rhythm of the book conveys a deep sense of purpose and a poetry beyond the often modest subjects depicted.

—Phillip Prodger

Head of Photographs, National Portrait Gallery

Head of Photographs, National Portrait Gallery

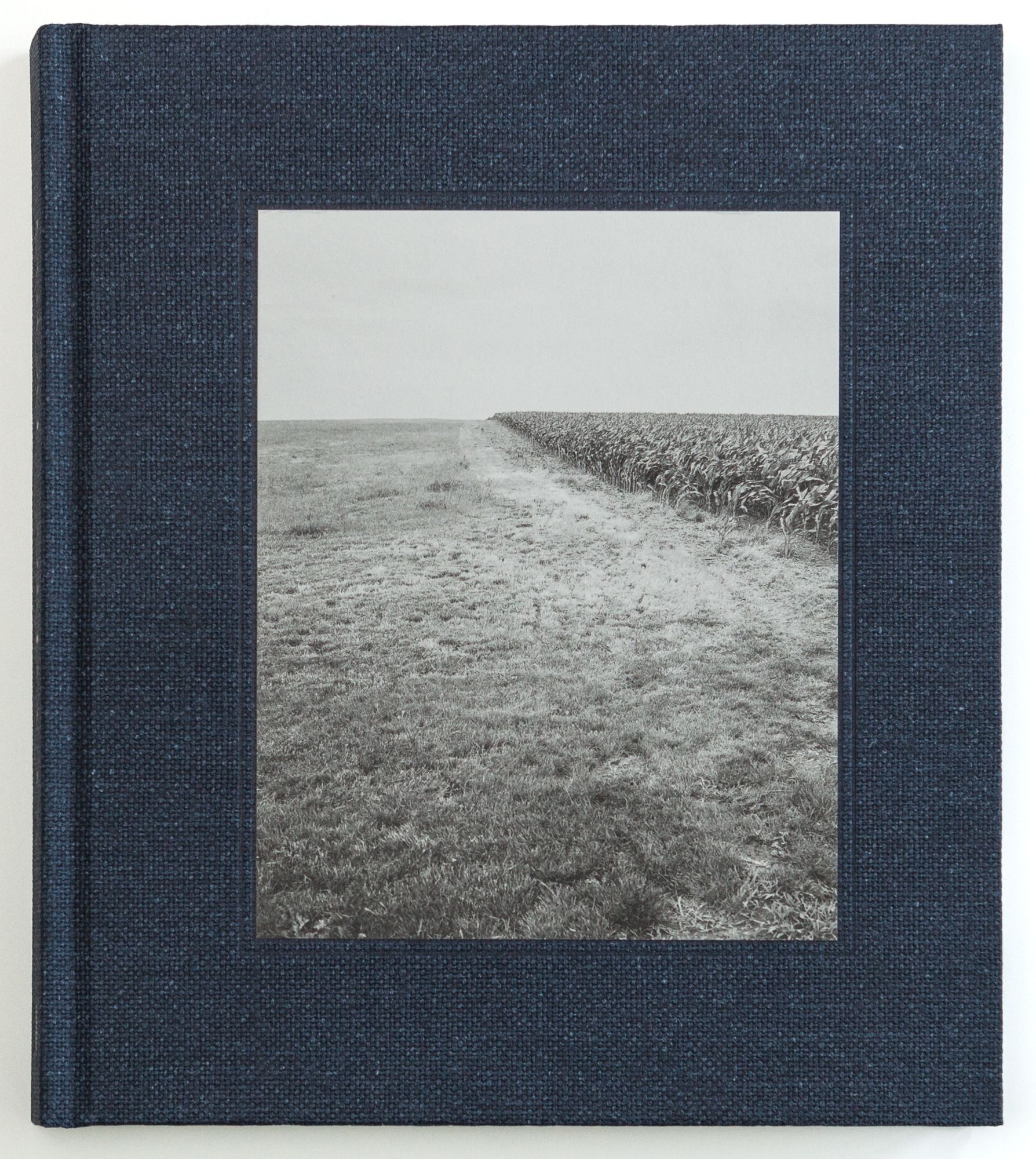

Local Objects feels like a quiet walk through the neighborhood we all grew up in. Carpenter’s ability to make you slow you down and focus on the subtleties of life rightfully places him in the lineage of Robert Adams. Ice Plant only accentuates that connection with a clean, elegant design—one of their best books yet.

—Chris McCall

Director, Pier 24

Director, Pier 24

I admire obsessions that lead to fruitful ends, in this case, Adriana Groisman’s Voices of the Tempest. Not being present for the Falklands / Malvinas conflict in 1982 that so dramatically affected Argentina’s history, Groisman began in 2003 to photograph the traces of conflict on the island and its violent surrounding sea. The latter included the search for the sunken Argentine war cruiser ARA General Belgrano that cost 323 lives.

Groisman interviewed the island’s residents and military combatants of all rank, both British and Argentine. I laughed over the woman who waved a white goose as her only available way to signal the advancing soldiers that she surrendered. I was moved by the Argentine pilot who, hoping for closure, sought out his British counterpart after the war even though that pilot had shot down two close friends. Strong photographs, engaging text, welcome addition to understanding the never-ending cost of war.

Possibly the most complex (and genius) conceptual book which accompanied a museum exhibition in 2017—Edgar Martins’ Siloquies and Soliloquies on Death, Life and Other Interludes. Notions of death and forensic material gathered during many years of research combine to make this compelling and extraordinary work, visually and intellectually.

—Zelda Cheatle

Independent Curator

Independent Curator

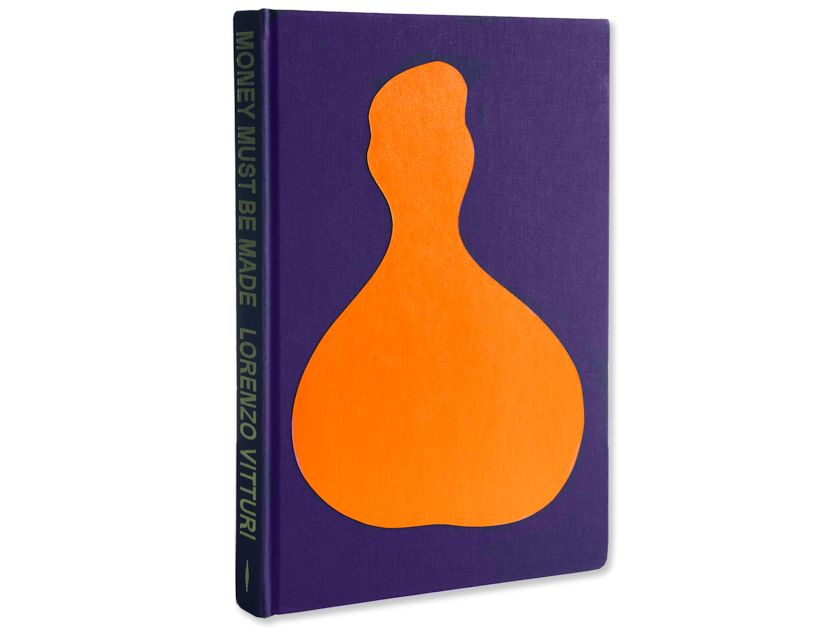

Lorenzo Vitturi was a student of mine at La Fabrica in 2006. From his very first steps, his curiosity for exploring his surreal images was evident. By putting in contact his forms, subjects, and sublime subjects, he created a truly original vision. In his latest work, Money Must Be Made, he utilizes, with great wisdom, the colors of the Italian Renaissance.

Museum Bhavan is an interesting experience between publishing and the museum, where a book has the same value as a piece of art in an art gallery. The book becomes an exhibition and the exhibition becomes a book: actually a “book-object.” The 10-volume box set is a hybrid catalog-book-display object. It is a private museum made public, an example of contemporary taxonomy.

—Alessandra Capodacqua

Independent Curator and NYU Florence Instructor

Independent Curator and NYU Florence Instructor

For more than twenty years, Anne-Marie Filaire has been building a body of work that is dense, engaged, rigorous, and monumental. Her first series, made in the ’90s in her native region of Auvergne, opened her to the subject of landscapes, leading her on a longterm personal and photographic quest. In this permanent movement between time and space, between history and the present, sounds an underlying violence. Far from the blinding moments of conflict, the distant horizons encounter the confinement of inextricable political situations.

Her latest, Zone de Sécurité Temporaire, is a necessary book that focuses on a political subject with a poetic gaze. Definitely worth being discovered.

—Fannie Escoulen

Independent Curator and Artistic Director of Prix Levallois

Independent Curator and Artistic Director of Prix Levallois

I spotted Mary Frey’s book, Reading Raymond Carver, recently at Medium Photo Festival in San Diego and was immediately hooked. The moments captured are so good they seem too good to be true—because, mostly, they are. In 1979, Frey was fresh out of a graduate photography program, pregnant and with her first teaching job. She used her family and neighbors to construct funny but relatable scenes, purposefully mimicking 1950s Good Housekeeping and LIFE imagery of the prototypical nuclear family. There is a boy in a basement holding his volcano project; a mother and child eating Raisin Bran; sisters listening to disco records; women smoking cigarettes with kids in laps. Looking back from almost 40 years later, nostalgia contributes to this book’s excellence but doesn’t supersede the quality of her beautifully crafted photographs.

—Alyssa Coppelman

Independent Curator and Editor

Independent Curator and Editor

Bleu is an immersive journey into the textures, colours and patterns of skin. This wonderfully tactile photobook absorbs the viewer in an abstract world of flesh. Marie works at the intersection between sculpture and photography and it’s fascinating to see how she has resolved these two interests through the form of the photobook.

—Sarah Allen

Curator, Tate Modern

Curator, Tate Modern

The Ward, Gideon Mendel’s documentation of the first ward in the UK dedicated to HIV/Aids patients in the early 1990s, is both moving and poignant. The size and the design of the book is intimate and quiet, and the testimonies of doctors, nurses, partners and family members of the dying patients provide a heartrending context to Mendel’s tender images.

Darren Harvey-Regan predominantly works with photography in spatial exhibition arrangements. This is his first photobook. Originating in the artist’s desire to liberate himself from the weight of representational imagery—a yearning for abstraction, The Erratics combines observed photographs of naturally occurring stone formations with carefully crafted records of studio-based chalk sculptures. Together with a new text piece by the artist, the book achieves more than a simple translation to print format; it extends the process.

—Chris Littlewood

Director of Photography, Flowers Gallery

Director of Photography, Flowers Gallery

“Baybay da lyuli!

Would you die tonight.

Tomorrow the frost will come—

We’ll carry you to the burial ground.

We’ll weep and wail,

You’ll sleep in a grave.”

Would you die tonight.

Tomorrow the frost will come—

We’ll carry you to the burial ground.

We’ll weep and wail,

You’ll sleep in a grave.”

This is one of the so called “deadly lullabies”—the phenomenon that I dedicated my first academic text to back when I was 18 and studied folklore. Lullaby 1 by Ukrainian artist Katya Lesiv has nothing to do with this peculiar genre. The artist told me that a lullaby for her “is something that can come only from a loving person, a wish of warmth, quietness and protection. It’s about relaxation. It also can be addressed, besides human beings, to spaces, events, feelings.”

Clearly, I see the subject and the book in my own way. Specific verses and associations come to mind. They are very far from what the artist meant by the work, and I am thankful for the space for interpretation that is left by the publication. I want to highlight Lullaby 1 not because it’s the best book of 2017 (I don’t believe in such a category), but rather because it caused in me a very subjective reaction that I will never be able to describe in the framework of 150-200 words. I can’t but mention the formal qualities of the book: elegant edit, beautiful riso print, and the fact that it belongs to a larger Lullaby project that deals mostly with graphic art.

A long time coming (in the best way), Small Town Inertia proves that you needn’t chase the big smoke, the big names or the big bangs to make important work that speaks universally. From the town of Dereham and the surroundings, Mortram has made work that should remind us of our deep connection and responsibility to our neighbours.

—Pete Brook

Independent Writer and Curator

Independent Writer and Curator

“My parents, who owned a photo studio, went missing after the 2011 tsunami. After the disaster, I found my father’s lens, portfolio, and our family album buried in the mud and the rubble. One day, I tried to take a landscape photo with my father’s muddy lens. The image came out dark and blurry, like a view of the deceased…”

The Restoration Will is a book about resilience: in psychology, it’s the ability to live, to succeed, to develop in spite of adversity. Looking at this extremely moving book, you can perceive something heartwarming. You can feel the “mental restoration” one may experience after a devastating event. This is Mayumi’s goal and she accomplishes it splendidly.

MISHO is an intimate, elegant book and very well-made. The book was silkscreen-printed with a photo-luminescent ink that allows the images and text to be seen in the dark.

I would like to heartily recommend my favorite photo book of the year: Internat by Carolyn Drake.

I bought my copy in advance many months ago, and receiving it a few weeks ago was revelatory. It is brilliant—from the fold-away cover to hand-colored spine to the genre-busting photography that veers from documentary to fine art and back again.

In her words: “This series was made at a Soviet-era orphanage designed to protect and provide shelter to girls marked as disabled. I actively collaborated with the residents, drawing ideas from fairy tales, and seeing where their joint aspirations led while passing time in the seclusion of the institution.”

Nothing else I saw this year came close.

—Rebecca Horne

Independent Writer, Producer, Artist

Independent Writer, Producer, Artist

The young photographer takes us with him to the dark side of globalization and shows us the shocking effects of the use of glyphosate herbicide spray in his home country (Argentina) for decades. The Human Cost is a brave book at the right time, that dares to ask questions about the limits of the habits of consumption in the Western world.

—Katharina Mouratidi

Artistic Director, Society for Humanistic Photography

Artistic Director, Society for Humanistic Photography

Sentieri is a wonderful, poetic, handmade book about nature. It includes photos of landscapes and found objects, watercolors, drawings and text. A book you want to look at very often. In an edition of only 50, with numbered and signed copies.

Atenea is a small but powerful book, which, in bright colours and big fonts, takes us on a journey through the Euro-powered EU. With a souvenir pack of one million “fake” euros in his backpack, Roger travels from the European Central Bank HQ in Frankfurt to the Parthenon in Greece. A real and symbolic journey from the financial power to the traditional values behind the EU, from wealth to crisis, from finance to daily life. I love how the images play with each other from page to page, and I adore the large-format words that streamline the story. No extras, just essential basics.

A collection of seemingly quiet portraits which pack an immensely powerful punch, in There Are No Homosexuals in Iran Laurence Rasti has beautifully photographed a community pushed into hiding by their own people. The limbo experienced by gay Iranians stuck in Denizli, Turkey where anonymity is their best protection from persecution is astutely captured by Rasti, leaving the viewer keenly aware of the dangers which lurk in the silence of their struggle to stay safe.

Jamie Hawkesworth’s new photo book Preston Bus Station is the final result of a project dear to his heart. Just like the photo series itself, the design of the book was years in the making.

The book represents Jamie’s work in its purest form, as it lets the photographs speak for themselves: there’s no introduction, there are no texts, no captions, not even a biography of the photographer, just a small colophon. It is a photobook in its purest form, giving the images full exposure and by doing this becoming a contained object in itself.

The refined details of the book design and the color-saturated printing reinforce the impression of being in the “enclosed” world of Preston Bus Station, where Jamie walked around in an endless loop, with an exquisite—and very democratic—eye for detail. His sensitivity picks up on the gentle grit and glamor of daily life, and foremost, the individuality of the passengers of Preston who were given extra warmth: not only by his attention but also because of Jamie’s specific and special color palette.

—Nanda van den Berg

Director, Huis Marseille

Director, Huis Marseille

This book is part of the “History of Misogyny” project currently developed by Laia Abril. On Abortion is the first volume from this ongoing series. Here, Laia Abril observes women’s reproductive rights from the past to today, raising different questions related to ethics, taboos, society, culture, and what is visible and remains invisible. The research itself opens many issues that are still crucial in 21st century. The design of the book supports the variety of images and texts brought together in this volume.

—Nathalie Herschdorfer

Director, Museum of Fine Arts (Le Locle, Switzerland)

Director, Museum of Fine Arts (Le Locle, Switzerland)

Marin Karmitz presents a great lesson to all those collectors who shop for pictures according to the generalised “good taste” of their class and type. Karmitz couldn’t care less about shopping. He’s loyal to his artists, interested in a very wide range of imagery, devoted to telling the same kinds of stories that he told years ago as a photojournalist. His collection is his communication, and he wants to address the human condition, as directly as he can, with neither squeamishness nor euphemism.

Simple to say; not so simple to do. The catalogue, titled Etranger Résident, is the second publication to come from his enormous collection, and together they have just scratched the surface. We’re told that the Maison Rouge, a privately-owned contemporary art centre in Paris, will soon close down. We regret it; we’ll miss exhibitions of the caliber, courage, and class like this one. The catalogue does, in the portable form of a book, what the show did on its much larger scale: moves you to the pit of your boots in ways that are fresh but not the less profound for that. It was maybe my show of the year; and the book gives a worthy flavour of that.

—Francis Hodgson

Professor, University of Brighton and Co-Founder, Prix Pictet

Professor, University of Brighton and Co-Founder, Prix Pictet