Preface: I was fifteen when I first saw Bill Owen’s book Suburbia and thought, “wow this is too cool.” So then I wanted to take pictures just like his. Owens had notes in the back of the book that described the gear used: Pentax 6x7. Okay…

Since then, I’ve had more than my share of medium format cameras: Mamiyas, Bronicas, Hasselblads, and the lovely folding Plaubel Makina. I even had a short-lived marriage with the all-electronic Rolleiflex 6008, a very modern 2-¼ camera for its time.

One camera I keep coming back to is the “Bill Owens camera,” the venerable Pentax 6x7.

It’s a relatively heavy medium format 120/220mm roll film camera that produces large 6x7cm (2-¼" x 2-¾") negatives or transparencies. I keep gravitating back to it over the years because of the kind pictures I get with it: Beautiful tones, striking resolution, and the 6x7cm format which I find comfortable. It’s not as rectangular as 35mm, and not the perfect square of the Hassy and Rollei. it’s a ratio very close to an 8x10 print or negative, so you utilize every millimeter of the negative and print area when working with standard paper sizes. I like that economy of usage. They used to call 6x7cm the “ideal” format.

I like the simplicity of its design, and how the camera looks and feels. It’s a pretty impressive machine to behold: large and serious looking. Its substantial weight indicates a lot of metal usage; you can just feel its workhorse solidity. It’s a very basic camera in many respects, no superfluous bells and whistles. But it’s definitely no toy. It’s more like a 35mm camera version of The Hulk.

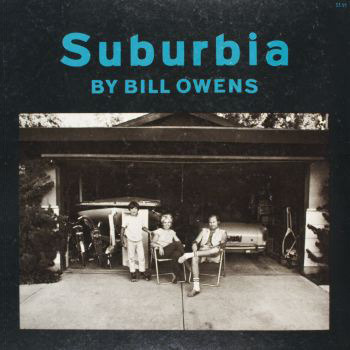

>>The original 1973 “Suburbia” pressing. The current pressing has a reworked cover that I am not too fond of.<<

So, the camera looks like a 35mm on steroids, and is similar in operation. It can take a prism finder, has a focal-plane shutter in the body, and a single throw ratchet lever for film-winding and shutter-cocking. Like the 35mm Canon F1, it too, is built like a tank. I like that. With the Pentaprism attached (plain or with meter), it weighs a lot. Which can actually make it possible to hand-hold it with longer shutter speeds. Its weight steadies your hand. I can shoot available light down to 1/30, and even 1/15 of a second with not much evident hand shake.

>> Early (but not the earliest) iteration of the venerable Pentax <<

The Pentax 6x7 was introduced in the late ‘60s and remained, but for a few small modifications, virtually unchanged for several decades. In the late '90s Pentax did an overhaul, and it became the 67II. Added were automatic aperture-priority metering, an LCD readout in the viewfinder and some other niceties. The auto-metering on the 67II has been widely hailed as spot-on (no pun intended), and I concur. Really great. Production of the camera ceased in 2009. Lots of the earlier incarnations are available on Ebay. The later 67II can be found, too, but usually at a premium price if it is in really nice shape.

>> Pentax 67II, a complete overhaul, was unveiled in the late 1990s <<

>> 67II with “newer” style 105mm lens.<<

Since its inception, the Pentax 67 (originally called 6x7, hereby referred to simply as “67”) was marketed as a machine that handled like an oversized 35mm slr. This is not untrue, especially with the eye-level prism (either metered or non-metered) attached. I can see that, for many, this would be a plus. Not necessarily for me, though. The camera is large and, for the way I work, I prefer not to be obscured by a camera held up in front of my face. So I tend to use the camera more like a Rolleiflex or Hasselblad using the well designed folding waist-level finder.

>> Favorite accessory: nicely designed waist-level finder <<

The waist-level finder lets me keep my head above the camera. Without a camera in front of my face, my feeling is that my subjects are more likely to be at ease, feeling less like an insect being inspected under a microscope. When in the studio shooting with 8x10, after I’ve composed and focused, I am off the the side of the camera to direct and engage the subject. So it’s natural for me to use the Pentax 67 and waist-level finder in a similar way, glancing down time to time to re-check focus and composition. Then I lift my head to talk with the subject I am photographing. I can do this without hardly moving the camera, and click when it feels right. With this finder, the subject is less likely to anticipate when I am going to shoot, often resulting in more interesting images.

>>Gordon, ©2013 Bruce Polin<<

Without the prism attached, the camera is a heck of a lot lighter and smaller. Better for transport. And, since I would mostly use the camera outside the studio (in the studio I would likely opt for large format), smaller and lighter is better.

>>Flippin’ your lid. Magnifier flips out of way to compose from above. Sporting the older 105mm lens style with knurled metal focus ring, which I kind of like. Personal preference.<<

>> With the waist-level finder folded closed. <<

Shooting with the waist-level finder on the 67, however, is not for everyone. It pretty much restricts your compositions to being horizontal only. Once you turn the camera vertically the finder points to the side. Not good. If you like verticals you’ll really need the prism finder. Or a square format camera. Since I tend to “see” horizontally it hasn’t been an issue for me.

There are times when I can’t resist using the auto-metered prism finder on the 67II …it’s such a pleasure to use. When I do, I like to use the beautifully crafted wood grip accessary. I find that it makes it easier to hold, but not everyone agrees. It’s a personal choice.

All of the camera’s iterations have had excellent build quality and fit-and-finish. The later 67II had more carbon-based plastic vs. the all metal and brass body/prism of the older counterparts, but it really didn’t diminish the professional build and heft. Some say the intelligent use of plastics improved the cameras’ ability to survive high impact knocks and falls. Possibly, but at the time I do remember feeling that they somehow cheapened the tank-like quality I admired of the original bodies. Do I still feel that way? Nope. I have both versions and love them equally. No complaints regarding build quality.

For me, the weakest part of the 67 system is its, sometimes tricky, film loading procedure. Unlike 35mm film, 120mm film doesn’t get wound back into cassettes after the roll is exposed. You have to remove the roll, put the used spool from the left to the right side of the camera, then load a new spool by threading the paper leader into a slot on the take-up spool. There are two problems that can occur here. First, both the new film spool, as well as the take-up spool, need to be positioned perfectly and locked in place. With the 67, sometimes it is not that easy getting the spools to engage the lock-in seat. You then have to spin the spools until they pop into place. Second, assuming your spools are seated properly, it can sometimes be difficult getting the paper leader to get properly “grabbed” by the take-up spool. You’re then forced to redo this process until it “grabs” the leader and starts to wind properly. There are definitely tricks to help avoid these issues, but be forewarned that it will require patience and practice. With this camera, if you try to load film too fast it will fuck up. Slow down.

>> Showing the two film spool locking rings. Finicky on occasion. <<

Other downsides? Slow x-sync for flash: only 1/30 second or slower. (Pentax made a few leaf shutter lenses that provided sync up to 1/500. You have to manually cock the lens shutter after each frame shot.) Also, the camera makes a pretty loud ka-plunksound. That’s a large mirror in there flopping about.

>> 165mm leaf shutter lens. One of two offered (there’s a 90mm as well) for faster flash sync. <<

Because of these limitations, most pros gravitated toward the Hasselbad system, with its faster flash sync with all lenses (they have leaf shutters in the lenses that sync with al speeds) and interchangeable film backs that you could pre-load for faster shooting with little down time. All valid reasons. These are unquestionably essential qualities for studio work that were shortcomings of the 67.

>>Leland, ©2013 Bruce Polin<<

That said, if you are comfortable working a bit slower and don’t have the above-mentioned studio requirements, the P67 is a well-made, reliable, albeit heavy camera that takes the superb and relatively inexpensive Takumar lenses. Remember, as opposed to systems like Hasselblad, you are not paying for a shutter each time you purchase a lens. Pentax 67 lenses tend to be really affordable. If you can get just one lens, it should be the 105mm f/2.4. It’s roughly equivalent to a normal 50mm lens on a 35mm camera. It doesn’t matter whether it’s the older version (knurled metal focus ring) or the later version (rubber focus ring), because they are optically identical. Both versions are pictured in this post. It’s simply a superb and extremely versatile lens. It’s also the fastest lens in the system. I could be quite happy with just this one lens; it’s what I use 95% of the time with the 67.

>>A good case: Pentax made a very good usable case for the 67 system. Holds two bodies, several lenses, film, etc. More storage in the upper lids, too. Hard to find in good shape.<<

So there you have it, folks. The hefty Pentax 67 can produce really great images. If you utilize light well and expose correctly, you will be rewarded with gorgeous negatives that can rival 4x5. But, like all machines and their owners, it’s not without its quirks.

No comments:

Post a Comment